CCSU in Brazil

Across Brazil, hundreds of thousands of residents known as Catadores have taken it upon themselves to reduce the amount of recyclables going into the landfill despite numerous obstacles.

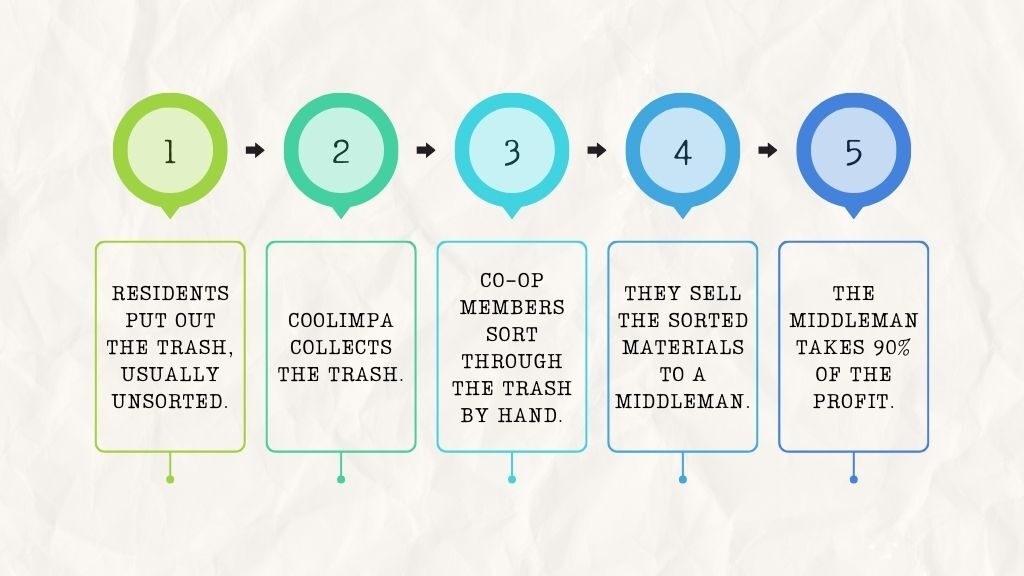

Paulo Henrique, director of Coolimpa Cooperative of Catadores, an independent recycling center in Ilhéus, Bahia, said that between 60 and 70 tons of recyclable material is diverted from landfills each month. The 32 Catadores who work there, including Henrique, sort through the trash by hand and use a middleman to sell the materials to companies that will recycle them.

“There was one week here, 15 days ago – we usually sell the material every week,” he said. “…For that week, it was R$129.10 ($23.19), for the whole week, for each.”

Henrique said that some materials, like glass, sell for up to 60 cents per kilogram, but the middleman takes 90%. Without funding from the city or government, the co-op has to use a third party to press and sell the recyclables.

Dona Diezemeire, president of Coolimpa, said that with money from the city, they could cut out the middleman entirely and go directly to the industry to sell what they collect.

“Today, we’re still passing it on to middlemen so they can send it to the industry, but the ideal would be for us to sell directly to the industry,” she said. “We don’t have a proper structure yet.”

Funding from the government would also increase their productivity. Diezemeire said that they only have one truck and go as far as 60 kilometers to collect trash. Because of the distance, she said that they can’t get there as often as they go to closer neighborhoods.

“We can collect 70 tons by hand, so if you had trucks to bring it all here, that would be 700 tons a month that wouldn’t go into the environment,” she said. “It could have been much better if the government had invested in the environment because, in reality, the aid isn’t for Coolimpa; it’s not for the cooperative members. It’s for the municipality, for the city, a tourist city.”

With financial help from the city, Henrique said that then they could finish building an enclosed center that would protect them against theft and invest in machinery that would make the process more efficient.

“The town hall, the help we get is a truck three days a week, but even when it breaks down, they’re not very interested in working together,” he said.

Unlike the United States, many areas of Brazil outside of large cities don’t have organized recycling programs. Instead, upwards of 800,000 independent waste pickers account for 90% of the materials that are recycled each year, according to the International Alliance of Waste Pickers.

Emerson Lucena, a biological science professor and the community integration coordinator at the State University of Santa Cruz in Bahia, said that the people of Bahia are moving toward a more organized system, with or without help from the government.

“After the creation of the Catadores cooperatives, especially in the city of Itabuna, there is more organization and support from the municipal government,” Lucena said.

Henrique said that support from the city was instrumental in the ability to rebuild after the Environmental Agents and Recyclable Collectors from Itabuna center in Itabuna, about an hour away from Coolimpa, was set on fire on Jan. 1. The center also fundraised within the community and on social media, according to their Instagram.

The fire was being investigated as arson, but the local authorities did not name any suspects, according to Itabuna City Hall’s website.

Lucena said that larger trash companies are paid by the ton for the amount of garbage they collect, and the Catadores take from their revenue with every gram of glass, plastic, metal and paper they collect, resulting in conflict between the two groups.

“If the waste pickers do their job and have the support of the population, the amount of waste to collect for these companies decreases,” Lucena said.

Henrique said that while they have never been attacked in the same manner, they have been threatened in the past and it’s common for people to steal what’s already been sorted. He attributes the theft to desperate people who would do anything to survive, but said the threats come from more unstable people.

“It’s really bad people – bad people who wanted us to pay them not to set fires here,” he said. “If people were aware of the impact that Coolimpa has on the environment, they would come and help.”

Despite the opposition, Henrique and Diezemeire said that they believe in the work that they are doing at Coolimpa. They not only help care for the environment, but they provide meaningful jobs for people in their community, Diezemeire said.

“It’s very important for the environment, obviously, but also for families because some people don’t have the ability to go to school; to university,” Diezemeire said.

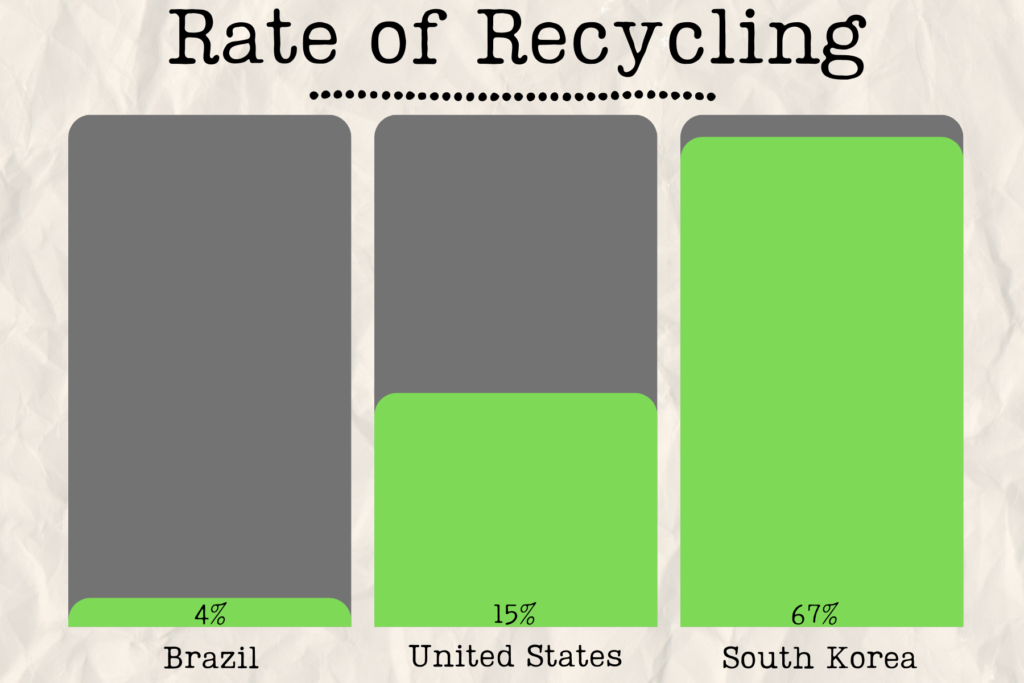

About 4% of the waste being produced in Brazil is being recycled, according to Agência Brasil. While 32% of Americans said they recycled in 2022, the amount of recyclables that make it to a recycling center is much lower, Smithsonian Magazine wrote.

Even though 32% of Americans say they recycle, World Population Review found that just 15% of solid waste produced in the U.S. was recycled in 2023. Similar to Brazil, some places in the U.S. are better at recycling than others. Getting accurate numbers is difficult because regulations are left up to the states and there are few rules at the federal level, they wrote.

Another contributing factor to the U.S.’s low percentage of recycling is a lack of knowledge; Americans don’t know how to recycle properly, resulting in items like unwashed plastic containers heading to the landfill instead, according to Columbia Climate School.

The Catadores at Coolimpa take care in pulling anything that can be recycled from the mixed trash they pick up and make sure that items are sorted properly and fit to be recycled, Diezemeire said.

“All this we’ve been doing by our own hand,” Henrique said.