CCSU in Brazil

Researchers say that cacao production in Brazil has been decreasing since 2015 because of climate change.

Plos One, a journal by the Public Library of Science, cited a survey that found the drought caused by El Niño in 2015 decreased cacao production by 89%. The drought also increased the rate of infection by witches’ broom, a disease that further harmed the production of cacao.

Cacao is a plant that is fermented, dried, crushed and grinded to make chocolate and cocoa. Jens Hammer, of The Cocoa Life Organization, said Brazil produced 430,000 tons of cacao annually in the early 1980s but now produces less than 200,000 tons a year.

Gerson Marques, owner of Fazenda Yrere, a cacao form in Bahia, Brazil, said cacao used to be one of the top three biggest products in the country, but he says cacao production is no longer a significant contributor.

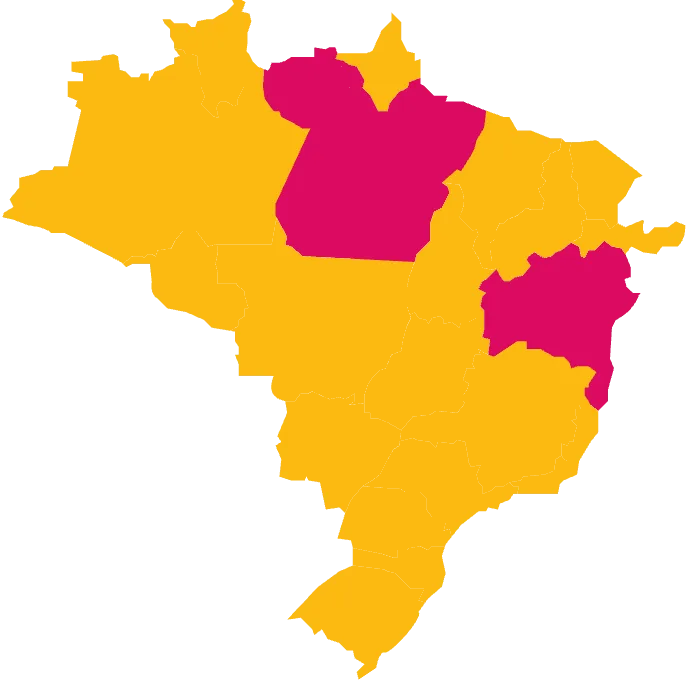

“In the past, it [cacao] was on of the big three from the Brazilian agriculture,” he said. “Today the production in Amazonia and Bahia holds the market in the country. Right now, we [Brazil] don’t export cacao anymore.”

According to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, it isn’t rising temperatures that are affecting cacao, it is the lack of humidity. Since many regions are facing drought, there is less moisture in the soil.

Marques said that the tourism and cacao are what hold his farm together and keeps it going.

Marques said climate change has been directly affecting his cacao production, which is causing him to look at different ways to adapt to the changing climate. He said that his farm experiences many extreme droughts, but sometimes, it also faces flooding.

He said that the method of Cabruca is self-sustaining in his farm and he has also been buying modified cacao seeds that stand up to extreme weather conditions. Cabruca, which is used by cacao farmers around the world, involves growing large trees next to the cacao trees to create humidity.

In Brazil, banana trees are typically used but some farms use a combination of large plants and trees that are typical to the region to create more production.

“The genetics [modified seeds] to fight witches’ broom came from resources from universities and companies like Embrapa,” Marques said, referring to The Brazilian Agricultural Research Corporation, which helps seeks innovations within Brazilian agriculture.

Marques said that these methods are helpful, but because of climate change, seeds are becoming more expensive.

“One of the problems that I am going through comes from Africa. The price of the cacao is really high because of El Niño, [which brings] a lot of dry weather,” Marques said. “So when it gets here, the price is really high.”

He said he makes his packaging more sustainable to cut down on costs while paying the expensive prices of the seeds to still make a profit.

Embrapa cites research that says large portions of the Amazon are facing all-time high temperatures while other parts now have new average temperatures.

“In the continent, of which the Amazon biome is an important part, 27% of undisturbed forest has had entirely novel regimes in mean annual temperature and 31% has experienced entirely new mean diurnal temperature ranges,” Embrapa reports.

It says that most of this heat is coming from climate change and the burning of fossil fuels, deforestation and forest fires.

At the Atlantic Forest in Brazil, these effects are also being seen, which has been affecting the cacao in its native region.

Célio de Sousa, a co-founder of the Floresta Viva Institute, an organization working to restore the Atlantic Forest, says they are also using Cabruca in their forest to help with the loss in cacao production.

“We can see that in 2015, we lost more than 200-thousand hectares of cacao because of the heat and there were problems during the process of the fruit, the process of the flowers from the trees, and two or three species changed,” he said. “This is because the more rain there was, the less it produced.”

De Sousa said that because of the changes in processes, he has been having to rely on Google to find out when he can plant certain agriculture.

“For example, in March is when they started to plant in order to harvest in July,” he said. “Nature is making its own calendar now.”

De Sousa said they would plant watermelon in August and would rely on the clouds and stars to see when it would rain. He said it is now unreliable and his organization has been having to use the internet to predict rain. He said the organization does not plan to combat climate change but is learning to adapt to its effects.

“The goal here is to [conserve] what’s working and, in the end, have a process of restoration,” de Sousa said.

Both Marques and de Sousa say that by educating people, they hope to bring about change and help reverse the effects climate change in Brazil and around the world.

You can see a 360 view of the cacao shop at Fazenda Yrere here.